The centennial of the Razi Institute; the snakes that saved the lives of American soldiers

Neda Sanij, BBC Persian – The Razi Institute was established in the winter of 1303 (1924-1925) during the late reign of Ahmad Shah, on the proposal of Mostafa Gholi-Bayat, the nephew of Mosaddegh and founder of the College of Agriculture in Karaj, and with the influential speech by Abdolhossein Teymourtash, the Minister of Public Welfare (Economy) in the Parliament.

It was decided that a specialist would be brought from France with a salary of four thousand Tomans to find a solution to this disaster. The Razi Institute was Iran’s entry point into modern agriculture. At the time of its founding, the Razi Institute was neither an institute nor named Razi; it was part of the Pasteur Institute complex, under the name “Institute for Animal Pest Control and Serum Production.

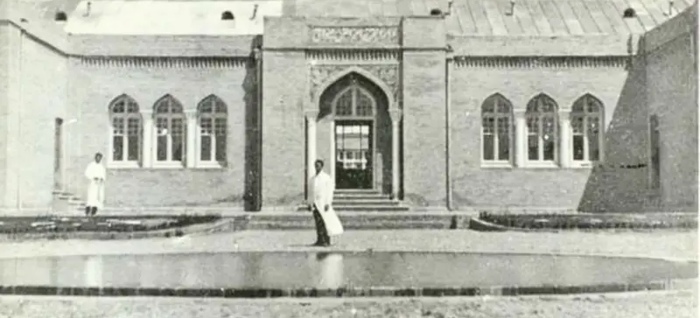

” The Pasteur Institute in Tehran did not have enough space for larger animal stables; therefore, the Razi center was moved to a village in Hashtgerd, Karaj, which had hectares of barren land around it.

The old residents of Karaj still know it by the name Serum-Sazi Hashtgerd. The name of the institute changed several times until, in the solar year 1325 (1946), Shamsuddin Amir-Alai, the head of the Ministry of Agriculture, proposed that it be named after Zakaria Razi, who discovered alcohol, in appreciation of his services; one of the few personal names given to public and government places that did not change after the revolution.

“Save my Cow”

In a historical film preserved from the Razi Institute, a farmer bitten by a snake named Rajab Ali is lying on a hospital bed. When he regains consciousness, he tells the doctor that he feels fine but asks to save his cow.

The narrator of the memorable documentary “Nishdaru” directed by Manouchehr Anvar says: “When Rajab Ali returns to the village, there will be no cow left. Up until three weeks ago, the cow was in good health. Its milk was regular, its appetite was good, it was lively. One or two days before Rajab was bitten by the snake, his cow fell ill.”

At the beginning of the 14th century of the Solar Hijri calendar, farming was the primary occupation for the people of Iran. Cows, in addition to providing meat and milk, were used by peasants for plowing. When cattle plague struck the villages, the cows would become feverish and lose their appetite, dying in a short time.

The famine and poverty following World War I were still ongoing, and farmers were frustrated. The government wanted to import cattle plague serum from France and Iraq, but the demand was extremely high. The “Institute for Animal Pest Control and Serum Production,” which wasn’t named Razi at that time, from its establishment in 1303 to 1306 Solar Hijri (1924-1927), managed to eradicate cattle plague with its production.

Then, locusts invaded Iran. Since the high cost of foreign currency was an issue even back then, this center had to shift from serum production to manufacturing locust poison.

The newspaper “Ettela’at” in February 1309 (1931) wrote about this: “Until now, the poison imported from abroad to combat locusts cost one hundred fifty Tomans per Kharvar [equivalent to 300 kilograms] due to the high price of foreign currency, and now, with the means to produce poison established at the Hashtgerd Institute [Razi], it costs us no more than seventy to eighty Tomans per Kharvar.”

With the help of the Razi Institute, by the Solar Hijri year 1309 (1930), the locusts were eradicated. However, unsafe drinking water, the lack of a sewage system, and poor sanitary and economic conditions continued to claim many lives. The Parliament decided that the Razi Institute should become independent and also treat humans.

In 1309, Mahmoud Fateh, the representative of the Ministry of Economy, during a trip to Europe, asked Dr. Louis Pierre Delpy, a French parasitologist, to take on the responsibility of the institute with its new duties. At the end of the 13th century of the Solar Hijri calendar (late 1920s), between 20 to 30 percent of deaths in Tehran were due to diphtheria, commonly known as “khanaq” in the vernacular.

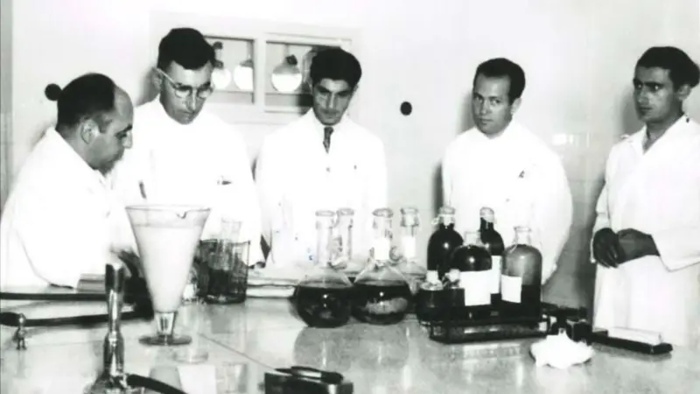

During World War II, diphtheria vaccine became extremely scarce, and the Razi Institute had no choice but to produce serum and then the vaccine. In the 1920s, Dr. Hossein Mirshamsi was tasked with creating the first Razi vaccine.

By 1325 (1946), the Razi Institute had produced both diphtheria and tetanus vaccines, which were its most important initial products. Gradually, with the efforts of Dr. Mirshamsi and his colleagues, vaccines for rubella, measles, mumps, and polio were also added to the institute’s repertoire, so that by then, six out of the nine essential and mandatory vaccines for children, amounting to 60% of Iran’s vaccine needs, were being produced by the Razi Institute.

The Queue of Snake Catchers in Front of the Razi Institute Building

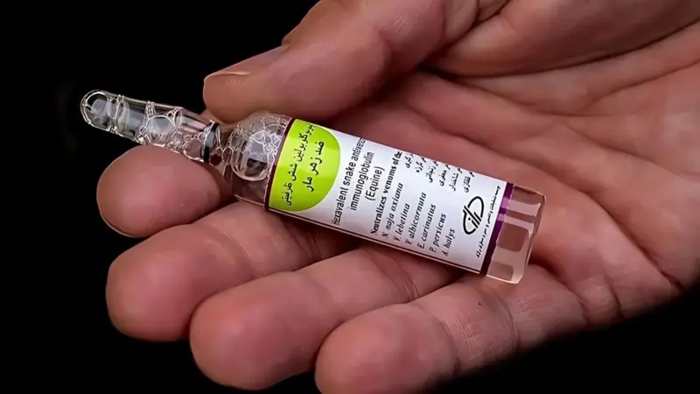

One of the achievements of the Razi Institute is that the dangerous snakes of Iran can no longer kill 150,000 people annually, unless the Razi antivenom is unavailable. When most of Iranian society was rural, snakebites were much more deadly. Sometimes they had to amputate the bitten limb, and still, the patient would die. In 1335 (1956), Dr. Mahmoud Latifi, a herpetologist, spent 10 years traveling across Iran to compile a national map of poisonous snakes and scorpions. He was bitten multiple times, and his fingers’ nerves were permanently damaged. At that time, Dr. Latifi was the head of the venomous animals section at the Razi Institute and later became an inspector for the World Health Organization.

When America Bypassed Sanctions for Snake Venom

When American soldiers were fighting in Afghanistan, antivenoms from the Razi Institute were sold to America for use by military doctors. According to a report by The Wall Street Journal, published in New York, the U.S. Army purchased 110 antivenoms through a third party in the period starting from December 2010 (Dey 1389).

The managers of the Razi Institute consider the sale of antivenom for $310 as one of Razi’s achievements. Antivenoms are typically made from animals native to the same region and specifically for the bites of those animals. According to the U.S. Army’s estimate at that time, around 110,000 coalition forces in Afghanistan were annually at risk of snake bites and other dangerous animal attacks.

A clinical study by several American researchers on snakebite victims admitted to three hospitals in Afghanistan in 1389 (2010-2011) showed that among the available options from France and Britain, Razi’s antivenom was the best antidote for Afghan snakes. Based on the Wall Street Journal’s report, the U.S.

Army had recommended the use of Razi Institute’s antivenom at its facilities in Afghanistan. The American newspaper, noting the sanctions and the prohibition of trade with Iran, wrote, “One of the ironic sidelines of the Afghanistan war is that the U.S. Army had to rely on the research arm of the Iranian government [Razi Institute] to combat snakebites.”

The primary product of Razi continues to be animal vaccines and antivenoms, which it has been able to export to countries in the region. However, Razi’s human vaccines did not enter the global market, leading to criticism of the institute after the revolution. Many vaccine production lines were halted, and the highly publicized effort by the institute to produce the CovPars vaccine for COVID-19 did not have a successful outcome.

February 4, 2025 | 3:56 am